Step 1.1 Getting agreement to do Systematic Outcomes Analysis

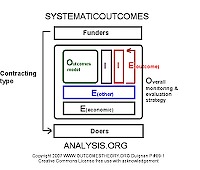

The first step in Systematic Outcomes Analysis is getting agreement from stakeholders to start building an outcomes model (creating the Outcomes Model Building Block). This is a model of the cascading set of causes in the real world for the area in which you want to intervene. Ideally you should try to get as much buy-in as possible from the highest level of stakeholders/management you can. You can use the introductory presentation on Systematic Outcomes Analysis to show what the process is all about. Even if you cannot get enough buy-in for the whole process, sometimes you can get agreement for you to start by just building an outcomes model. When the benefits of using the model are seen, you can then move on to developing the other building blocks of Systematic Outcomes Analysis. Motivations for using the approach can differ. Sometimes it can be because people want to use the system only for strategic planning; sometimes for monitoring or evaluation planning; sometimes for thinking about the possibilities for economic evaluation; and sometimes for working out what should be done regarding outcomes-focused contracting. It does not really matter what the initial motivation is for doing Systematic Outcomes Analysis; once some of the building blocks are in place, it becomes clear to stakeholders that they can use the approach for meeting a range of their core organizational needs. Regardless of why you are doing Systematic Outcomes Analysis, the first step is always building a robust outcomes model, you do this in the following way:

1.1.1 Hold a meeting of the wider group of internal stakeholders who are interested in an outcomes model being built and explain the Systematic Outcomes Analysis approach to them (you can use the introductory presentation).

1.1.2 Get agreement from the wider group to set up a smaller working group to actually build the outcomes model. This should include the highest level or stakeholder or manager you can get; someone who knows how to draw outcomes models (i.e. who has studied the outcomes model standards); and two to four content specialists. Building models with groups larger than this is often difficult. Others can be called into the small working group building the model as their specific expertise is needed. Typically, developing the model will take a three to four meetings held once a week. These meetings should allow sufficient time for participants to get focused on the task at hand. The meetings should usually last less than two hours, but not longer than half a day, this is because the work requires close concentration. Additional people can sit in on the meetings if they are interested in finding out how the process works.

Step 1.2 Drawing a comprehensive outcomes model in the smaller working group

The way in which the model is developed is important. If artificial constraints are put on the type of outcome that is allowed to go into the model (e.g. only measurable and attributable outcomes) then it is likely that the model will be useless for later stages of the Systematic Outcomes Analysis process. To make sure that the model is built in the most useful way possible, the model should conform to the Systematic Outcomes Analysis outcomes model standards.

Step 1.3 Checking your model with stakeholders

Once the smaller working group has developed a draft of the outcomes model, it should be checked with the wider group of external stakeholders and then with other groups of external stakeholders.

1.3.1 Checking back with the initial wider group of internal stakeholders should take place relatively early in the development of the model to make sure that the smaller working group is on track (say after the smaller group has had three meetings). There should be a brief introduction to the wider group making it clear that in Systematic Outcomes Analysis, the outcomes model should be of the real world and can contain not currently measurable or attributable outcomes. It should also be made clear that the model is only a draft, however it should be presented in a tidy format so as to avoid members of the wider group making too many minor changes. A tidy format makes it feel that the model should not be amended unless there is good reason to do so. The emphasis at this stage is both on the outcomes and links within the model but also on whether the smaller working group has got it right in terms of the way it has divided outcomes up into conceptual groups (or slices - see the outcomes model standards). This stage of developing the outcomes model may need more than one iteration, with the small working group going away and working on the model further and then bringing it back to the wider group several times.

1.3.2 Checking with external stakeholders. Once you have the outcomes model at a stage where your organization is happy for external stakeholders to see some of it as draft material, then you should take it to whatever groups of external stakeholders are relevant to the project. Remember to always brief them on the fact that in Systematic Outcomes Analysis it is fine for an outcome model to contain not currently measured or attributable outcomes as the purpose is to draw a model of the real world. The model is not just about what you can currently measure or prove that your organization has influenced. External stakeholders are usually able to relate to such more comprehensive models much better than ones which just focus on measurable and attributable outcomes focused just on an individual organization's perspective.

Step 1.4 Check you model against existing empirical research

The outcomes model you have drawn so far, and which you have checked with your stakeholders, is your (and your stakeholders) claim about how the world works regarding the interventions you are planning or currently undertaking. It may or may not be an accurate representation of how the world actually works in practice. It is in this step that you check you model against existing empirical research. What we mean by empirical research at this stage in Systematic Outcomes Analysis is simply research which relies on observations made of the world, rather than just on reasoned justification. We first check the model against empirical research and then, secondly, against reasoned justification. How extensive this process of checking is, depends on the circumstances.

1.4.1 Check your model (the outcomes and the links between them) against existing empirical research either yourself, if you have the skills to to do this, or by getting someone else to do it (e.g. experts in the field, university researchers etc).

Step 1.5 Develop reasoned justification for parts of your model where there is no existing empirical research

There is unlikely to be existing empirical research for every link between outcomes in your model. You therefore need to develop a reasoned argument for those links for which there is no existing empirical research. It is a mistake to only allow links in models which can be supported by empirical research. The is because different outcomes models and different parts of a particular outcomes model vary in the ease with which they can be validated using empirical research. If you inappropriately limit yourself to strictly empirically based models you can end up only doing that which is empirically able to be validated rather than doing what seems to be the most strategic thing to do a particular situation.

1.5.1 Develop reasoned justification for any parts of your model which are likely to be challenged by stakeholders. This justification only needs to be as extensive as is appropriate. For instance, there may be many instances in your model where the link between outcomes is obvious to stakeholders. You do not need to set out justifications for all of these links.

Step 1.5 Turn issues needing further work into outcomes model development projects

There are likely to be aspects of your outcomes model that need further work. For instance, developing more detailed outcomes in a particular area of the model; developing a further slice (a slice is simply a grouping of conceptually related outcomes e.g. national level, locality level, organizational level etc) in an area; or doing a literature review to look at the empirical evidence beneath one part of your model. All this work can be turned into outcomes model development projects.

1.5.1 Look at the state of development of your outcomes model, identify what further work needs to be done, and turn this work into outcomes model development projects. These will have to be prioritized later, together with the other projects which emerge from other parts of your Systematic Outcomes Analysis.