Principle: Outcome measurement where an outcome is controlled by only one other outcome is sufficient for attribution - in the case of an outcome controlled by only one other outcome (intervention) the mere measurement of the outcome is sufficient to attribute its change to its controlling outcome (intervention) [Provisional only].

Principle: Outcome measurement where an outcome is influenced by more than one other outcome is not sufficient for attribution - in the case of an outcome influenced by more than one other outcome (intervention), the mere measurement of the outcome is not sufficient to attribute its change to one of its influencing outcomes (interventions) [Provisional only].

Discussion: This principle is violated in those outcomes systems where it is believed that mere measurement of a set of outcomes (regardless of whether they have been established as attributable indicators (I[att]) is regarded as evidence of attribution.

Principle: Attribution of an outcome to an intervention is not sufficient for holding an intervention organization accountable - attribution of a change or a lack of change in an outcome to an intervention organization is not, on its own, to hold the intervention organization accountable.

Principle: Accountability requires intervention organization's reasonable autonomy in intervention selection and non-extraordinary conditions - An intervention organization should only be held accountable for a change or a lack of change in one or more outcomes if it has reasonable autonomy in intervention selection and no extraordinary factors have occurred.

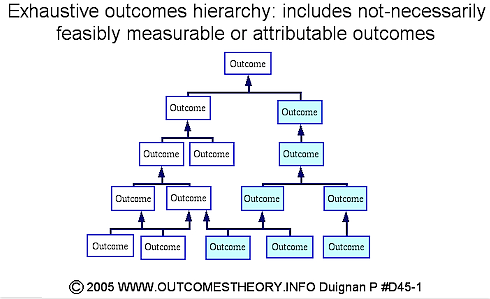

Principle: Including not-necessarily feasibly measurable or feasibly attributable outcomes in an outcomes hierarchy can provide strategic advantage - Within outcomes theory, exhaustive rather than truncated outcomes hierarchies are drawn. Truncated outcomes hierarchies only include outcomes which are measurable and attributable whereas exhaustive outcomes hierarchies include all of the hypothesized 'cascading set of causes in the real world' regardless of their measurability or attributability in a particular setting. An exhaustive outcomes hierarchy often provides strategic advantage over a truncated one because it encourages intervention effort to be directed at both all relevant intermediate outcomes regardless of whether they are measurable or attributable. [Provisional only].

Discussion: Outcomes hierarchies can be drawn as either exhaustive hierarchies which include not-necessarily measurable and attributable outcomes or truncated outcomes hierarchies which do not. An historic emphasis on measurability and identifying routinely attributable indicators has resulted in many outcomes systems demanding that only measurable and attributable outcomes be considered. An exhaustive outcomes hierarchy is illustrated in the diagram below.

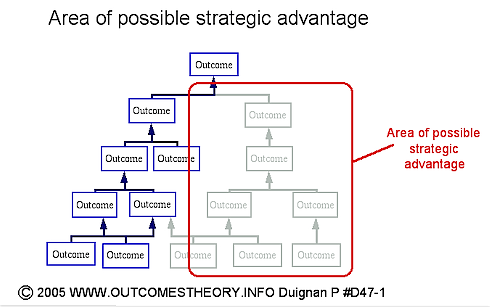

A truncated version of this outcomes hierarchy is shown in the diagram below. The grayed-out outcomes are not included in this outcomes hierarchy because they are non-measurable and/or non-attributable.

An exhaustive outcomes hierarchy can provide strategic advantage over a truncated outcomes hierarchy, this is illustrated in the diagram below.

In non-competitive situations, such as much public sector activity, using an exhaustive outcomes hierarchy can provide strategic planning advantages. In the diagram above, the grayed-out boxes would not appear in the truncated version of the outcomes hierarchy. Developing strategy on the basis of the truncated outcomes hierarchy would mean that the possibility of using interventions directed at the grayed-out boxes would not be considered. As in this outcomes hierarchy, the non-measurable and/or non-attributable pathway may be a necessary set of causes which are needed in order to achieve the highest-level outcome.

In competitive situations, it is likely that the strategic pathway which is feasibly measurable and attributable has been well exploited by many players. If a player is able to intervene in the area of the outcomes hierarchy which has previously been ignored because of the difficulty of measurement or attribution, then in some situations they may be able to achieve a strategic advantage. [Provisional only].

Principle: Strategic selection between interventions based on outcome attribution needs to take into account ease of attribution.

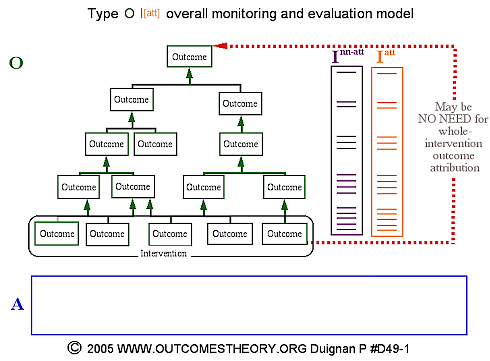

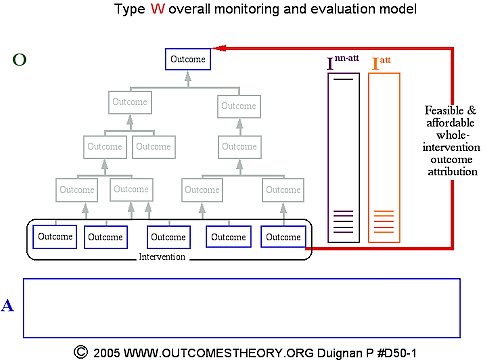

Discussion: Within the evidence-based practice movement there is often the demand that strategic decision-making between interventions be based on the available evidenced regarding attribution of changes in high-level outcomes to interventions. In some cases the information used for such decision-making is restricted to information from whole-intervention high-level outcomes attribution evaluation designs (W), often of a restricted type, e.g. randomized controlled trials. Such an approach is reasonable in those cases where the ease of undertaking such designs is reasonably similar across all of the interventions being selected amongst. This is the rationale for using such an approach in instances such as the selection of pharmaceutical. However, it is not reasonable to apply this approach when attempting to select interventions from amongst a set of interventions which differ significantly in what is possible in terms of their overall monitoring and evaluation model and in particular the feasibility, timeliness and affordability of whole-intervention high-level outcome attribution evaluation designs (W) within those models. For instance, the models below set out three different overall monitoring and evaluation models. If the task of strategic decision-making is just to select between interventions on which either of the first two models could be used then it is reasonable, other things being equal (in particular the amount of monitoring and evaluation the interventions have actually received), to proceed to select the preferred intervention on the basis of the strength of evidence that changes in high-level outcomes can be attributed to a particular intervention. However, if the strategic decision-making also includes selection from interventions for which the first two models are not feasible or affordable and only models like the last can be used, then it is no longer reasonable to select the intervention just on the basis whole-intervention high-level outcomes attribution evaluation results. While this may seem self-evident to many, this is a major danger of an unsophisticated approach to evidence-based practice.

V1-2.